Ghosts in Napa

Nov 1, 2025

A few weeks ago we went on a little Napa trip with friends and stopped by a vineyard called Schramsberg. While our tour guide proudly mentioned the underground caves, all hand-dug railroad workers without dynamite, I noticed an old photo on the wall. In the corner stood an Asian man, a bit apart from everyone else, with a timid smile.

Photo at Schramsberg. Not dated.

Photo at Schramsberg. Not dated.

Later, walking through downtown Napa, we came across a plaque on the First Street bridge dedicated to “the last merchants of Chinatown,” honoring Shuck Chan, who operated Lai Hing Co., a mercantile store.

I knew nothing about Chinese history in wine country. Chinatown is obviously nowhere to be found here. So these little fragments of the past felt strangely surprising.

...

In the 1860s and 1870s, it is Chinese laborers who dug wine caves[1], built the Napa Valley Railroad, and formed Chinatowns in Napa, St. Helena, and Calistoga. But the population began to fall soon after. The Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 suspended entry of all Chinese labors. A series of suspicious fires followed, destroying major parts of these neighborhoods.

By 1929 Napa’s Chinatown was razed entirely for a proposed yacht harbor that was never built[2].

...

Who are these railroad workers? I started reading Ghosts of Gold Mountain by Gordon H. Chang.

The Central Pacific Railroad, which built the western portion of the transcontinental line from 1864 to 1869, employed roughly 20,000 Chinese workers, about 90% of the construction labor force[3] largely migrated from Guangdong province[4].

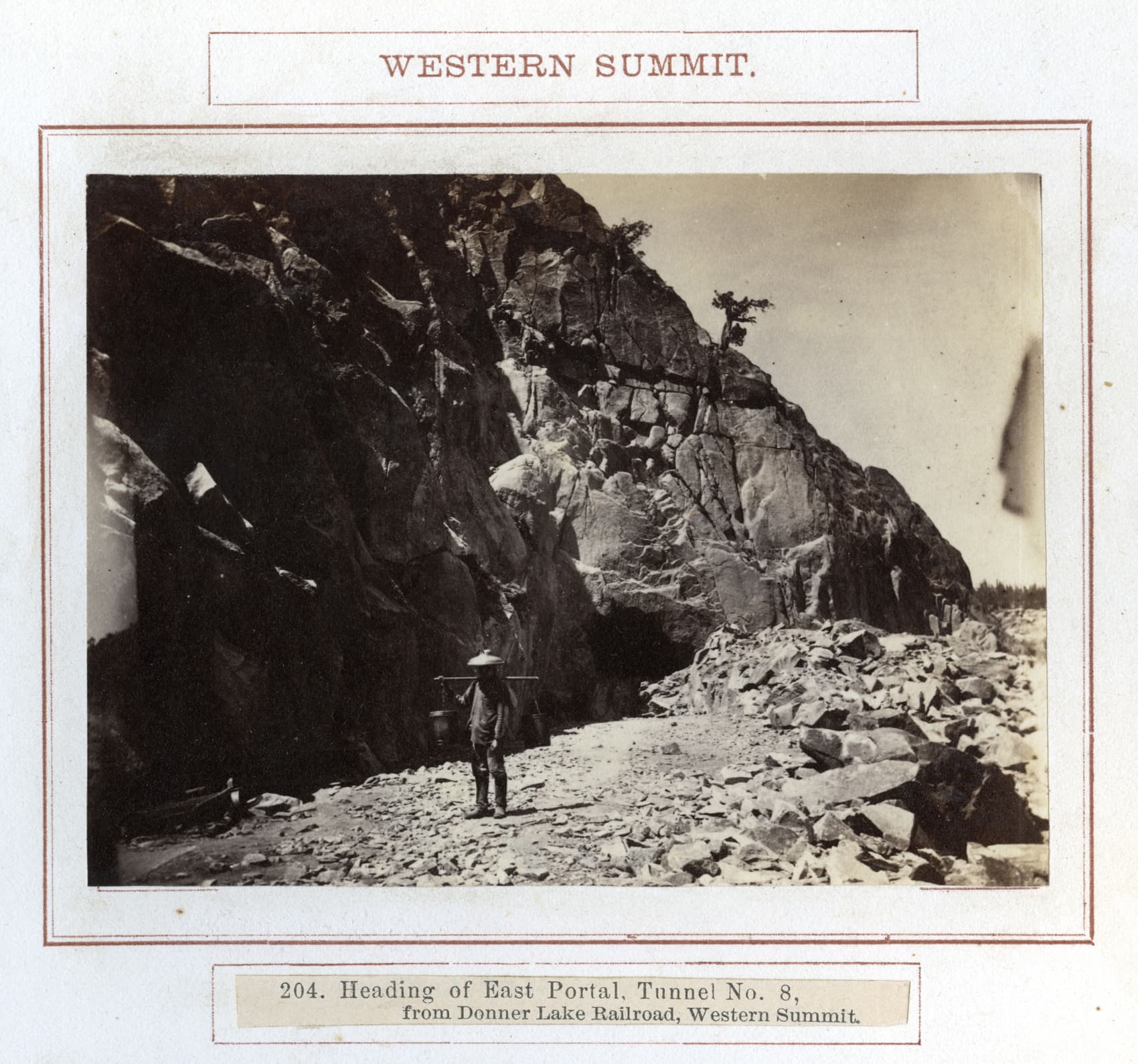

The western route was brutal. From Sacramento the line climbed more than 7,000 feet to Donner Summit. Workers had to cut through dense forests, blast granite, and carve tunnels while snow piled thirty feet deep. Thousands likely died from accidents, explosions, avalanches, and extreme cold[5].

20,000 workers, yet not a single personal letter, diary, or written account from any Chinese railroad worker has ever been found in the United States or China. Not a single one.

The transcontinetal railroad completely transformed the U.S. economy. But the voices of those who built it was nowhere to be found.

...

We rewatched Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor the other night, and it reminded me how helpless any individual becomes in the tides of history. I keep imagining one of those workers standing in the Sierra cold, thinking about home. There’s probably no snow in his village in Guangdong.

But I guess I’ll never know.

***